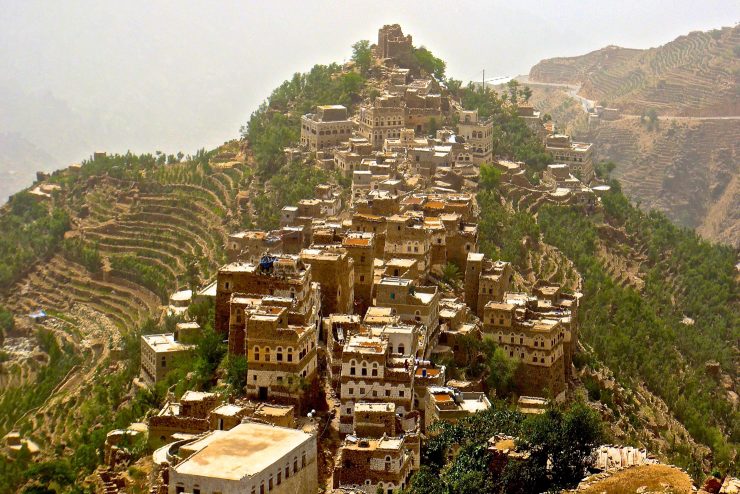

Terraced lands growing coffee in Yemen

As the conflict in Yemen between a US-backed, Saudi-led military coalition and the Houthi militia enters its third year, life for civilians in the country has never been more dire. The war has already left over 10,000 dead, 40,000 wounded, and more than 3 million displaced, according to United Nations estimates. But while the West has been militarily involved in Yemen for years, with the Bush administration ordering drone strikes there as early as 2002, only in the past months has concern with the humanitarian crises in the Middle East’s poorest country begun to build to something of a chorus.

First, at the end of January, there was the Trump administration’s raid on a rural, central-Yemeni village that cost the lives of 25 civilians including nine children and eight women, in addition to that of a US soldier. The raid is still being reported on and in many cases criticized by government officials, human rights organizations, and the media.

Then, in the middle of February, the UN released a report declaring Yemen on the verge of famine, with 90 percent of civilians in the country in need of some form of humanitarian aid and more than 450,000 children currently suffering from severe acute malnutrition—“a nearly 200 percent increase since 2014,” the UN says. Illustrated another way, right now, one Yemeni child dies of preventable causes, like hunger, every 10 minutes.

This humanitarian crisis appears set to only worsen with the continuation of an American-supported Saudi blockade on imports to some of the most hard-hit areas in Yemen, in addition to a continuation of the two-year-old Saudi bombing campaign that has destroyed critical infrastructure, schools, hospitals, and razed civilian gatherings including weddings and funerals.

We offer this context because, in the midst of this, the international coffee community is right now having something of a moment of renewed interest in Yemeni coffee. Although the country was the first to commercially cultivate coffee in the 15th century, only in the past five years or so has there been a strong interest from specialty coffee companies abroad in buying, roasting, and serving Yemeni coffee.

Sprudge has written extensively about this connection before, but since the $16-a-cup Blue Bottle Coffee collaboration with Mokhtar Alkhanshali’s Port of Mokha last year, the demand for specialty Yemeni coffee has only expanded. Soon, you’ll be able to find what Alkhanshali advertises as “the world’s best coffee” at Equator Coffee & Teas, Dragonfly Coffee Roasters, Slate Coffee Roasters, George Howell Coffee, and Paris’ Coutume Café.

That such a historically important growing region, once a footnote as only that, is now receiving recognition for its ability to produce excellent coffee today is ostensibly good news.

But looming questions remain. Given the ongoing instability inside Yemen, what exactly will an increased demand for Yemeni coffee mean for Yemeni coffee producers? And moreover, what does it mean for Yemen’s overall economy given that the country is in the midst of a war?

Washington DC-based Al Mokha is attempting to answer those questions.

Al Mokha founder Anda Greeney

Founded in 2013 by Anda Greeney, a former Air Force Lieutenant and MBA student at Harvard, Al Mokha was created to function as both a coffee company and means of promoting economic growth and stability in Yemen.

“My gut instinct is that business is a great way to drive development,” Greeney says. He believes that to create growth in a developing country, homegrown solutions, not the provision of development aid, are necessary.

Al Mokha is Greeney’s way of facilitating one of those solutions in Yemen. By helping to drive demand for Yemeni coffee internationally, he hopes to expand the market in which Yemeni coffee producers can operate. This, in turn, will promote a natural expansion of coffee production in Yemen to historically high levels.

This is what Al Mokha refers to as a “one billion dollar opportunity,” the effects of which will not only benefit one million Yemeni citizens but will help stabilize internal conflict in Yemen by providing employment opportunities, whereas now there are few.

“How can markets, businesses, create jobs?” Greeney asks.

Named after Yemen’s historically most significant port city—the actual Al Mokha is now a fishing village, and currently the site of heavy military confrontation from which as many as 30,000 civilians have fled—the company is still small and relatively unknown; Greeney remains its only on-the-books employee.

“At the time the company was founded, I couldn’t travel in Yemen,” Greeney says. “So I ended up spending time in Oman. Then I moved to Boston to start this night Master’s at Harvard Extension, and the first semester there I was taking a research methods course and needed to write a final paper that would turn into a thesis later on. I suggested the idea of Al Mokha to my professor. And he said, ‘Sounds good. Okay.’”

Within months Greeney submitted the idea for his company to an entrepreneurship competition through the school and soon found himself with $500, buying green Yemeni coffee.

“I met with some roasters, roasted up some coffee samples, and we had 400 of these little sample bags,” he says. “And I’m not a coffee guy. I didn’t know anything about coffee. Didn’t know anything about roasting. I was like, ‘coffee beans are supposed to look dark and oily,’ and I started looking at these dry, lighter-roasted beans and was like, ‘that just doesn’t look right aesthetically, I don’t know if this is going to sell.’”

But he wouldn’t be here if it hadn’t. The Yemeni Embassy in DC is a regular customer. And Greeney’s found success selling coffee to customers around the US and internationally—including those living as far away, or depending on how you look at it as close, as Saudi Arabia and Oman.

“The remarkable thing still is that people like it,” Greeney says. “Coffee from Yemen, people just like it.”

Greeney serving Al Mokha to Yemen’s ambassador to the US

For the most part, Al Mokha doesn’t buy coffee when it’s still at origin, instead purchasing the majority of its green Yemeni beans when they’re already in the States.

“We have a reserve coffee, the Al-Wudiyan, that was a pre-purchase while it was still at origin,” Greeney says—it passed through the Rayyan Mill, an American-founded operation in the capital Sana’a known for its quality.

Greeney isn’t looking for his company to become the next Third Wave darling. Instead, he sees entering the mainstream coffee market as vital to not only the success of his business but for the expansion of Yemen’s coffee industry as a whole.

“A third of my customers are Sprudge readers, people who have good taste,” he says, laughing. “A third are Middle Eastern with ties to Yemen, and a third are just regular people who don’t drink Third Wave coffee. They may be open to it but they drink Folgers too. They drink my coffee and love it. We sell quite a bit of dark roast.”

In this way, Al Mokha doesn’t really compete with other American coffee companies specializing in the production of Yemeni coffees. Instead, Al Mokha is working alongside them toward the same end.

Measuring the impact of that production on Yemen itself, however, remains a challenge.

Dr. Erin Fletcher, an economist and international development consultant, and member of Al Mokha’s advisory board, says it’s an issue they’ve wrestled with since the start.

“How do we know if it’s working?” she says. “As an economist, I want a randomly assigned treatment and control group and want to talk to people before and after and during and know everything that’s going on. But that’s not really possible here. What we’re doing right now is figuring out what is the best thing to measure, and asking what is the best way to qualitatively and quantitatively assess impact.”

It’s this issue that initially drew me to Al Mokha. The desired outcomes of its work are far-reaching, but the tone with which they are presented is measured. Talking to Greeney and Fletcher, I understood where the two sides of the company’s proverbial coin come from.

“We definitely have some ways of thinking about what we’re doing and metrics that we can track year over year month over month, and ways of thinking about whether we’re meeting goals or selling more coffee or helping more farmers reaching more people,” Fletcher says.

“How do we put a price on impact?” Greeney adds. “We’ve got our model, now we’re going to build a business.”

The success of Al Mokha and others can’t come soon enough. In addition to the damage being done to Yemen’s civilian population by its war, there are tertiary effects of the conflict on the coffee sector.

Dr. Amin Al-Hakimi of Sana’a University explains that the incredible diversity of coffee varietals native to Yemen is at risk as more farmers abandon their cultivation for lack of profitability.

“We are trying to adapt to the conflict,” Dr. Al-Hakimi says. But he hopes it ends soon.

Dr. Al-Hakimi points to a need for a system that helps farmers market their coffee, incentivizing the preservation of the coffee sector for its economic significance.

Whether a more robust international demand for Yemeni coffee is the impetus for that system’s creation remains to be seen. But ordering a bag of coffee from Al Mokha is a vote of confidence that it is.

“The really important point,” Greeney says, “is that business is resilient. There’s a war going on, but coffee is still getting out. That’s what’s so important about how anyone thinks about development. The businesspeople in Yemen are creative, they’re going to take the steps necessary to keep getting coffee out.”

It’s that resilience I most hope Anda’s right about. Not just of business, but of the people behind it.

Michael Light (@MichaelPLight) is a features editor at Sprudge Media Network. Read more Michael Light on Sprudge.

Photographs courtesy Al Mokha and Rayyan Mill.

The post Amid Crisis, Al Mokha Brings Yemeni Coffee To The United States appeared first on Sprudge.