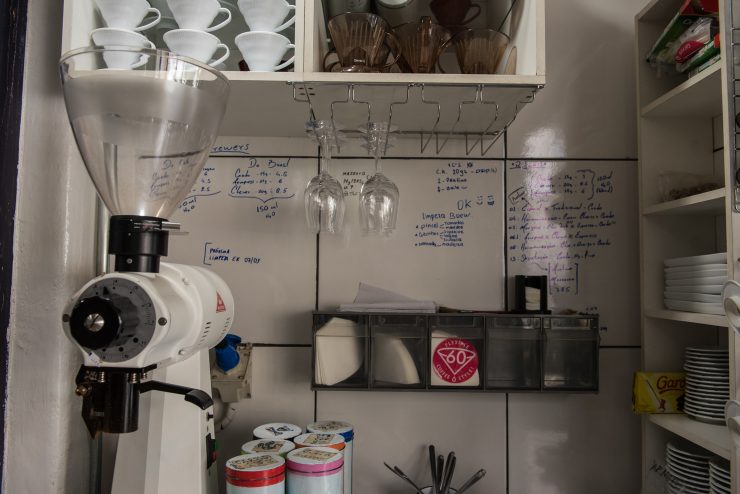

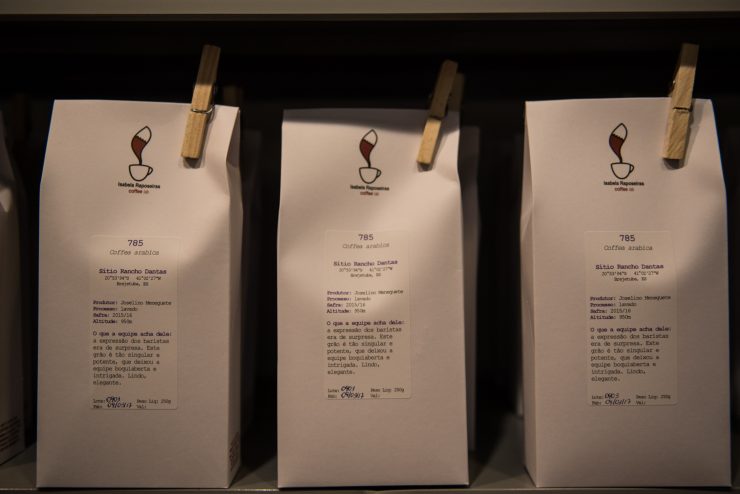

Airplane pilot, cigar aficionado, barista, Q Grader, shrink, first barista champion of Brazil: Isabela Raposeiras can be defined in many ways. In 2009, after seven years of consulting for coffee businesses, she founded Coffee Lab, Brazil’s most awarded roastery, in São Paulo. There, you will see baristas working in colorful jumpsuits, two Diedrich roasters in the middle of the service tables, and four classrooms (Coffee Lab is also a coffee school).

As a first-timer there, you will already be surprised when you order an espresso. The barista will bring two: one in a small demitasse cup and the other in a big teacup. The idea is that you see how that interferes with your sensorial perception. Raposeiras is the brain behind these coffee rituals offered at the Lab, which aim to show newcomers how specialty coffee differs from the commercial, low-grade coffee served in most of the country’s households. It’s been working pretty well: The coffee shop is always packed and the classes often fully booked. We talked with Raposeiras about her career, plans for the future, and her assessment of the Brazilian and global specialty coffee community.

How was Coffee Lab born? What was your story with coffee before?

I’ve been working with coffee since 2000 and doing consulting work in the field since 2002. I opened my consultancy/school headquarters in 2004, and Coffee Lab as we now know it was born in 2009. The idea was to open a roasting and training center here, but I couldn’t help but also establish a coffee shop in the same space. Since then, we have been getting most of the awards in this business, which I find to be rather sad. It means that no one else here has been innovating as much as we have.

But don’t you see more and more specialty coffee businesses opening here in Brazil today?

Yes, absolutely, but they are very similar to those we already have, which are often copies of foreign coffee shops. Scandinavian and American coffee shops are nice and have their idiosyncrasies that make them special and all, but that works there, not here. Here at Coffee Lab, we have our own way of doing things, I don’t know if that’s Brazilian or it’s our special way, but I have people from all over the world suggesting that we open a Coffee Lab in many places all over the world. I’ve thought about it, but currently my focus is 100 percent on our school.

What has significantly changed since then, both at the Coffee Lab work/service style and the Brazilian market?

From a consumer standpoint, I see more difference between the time when I started in coffee—17 years ago, when no one else was talking specialty coffee here—than since the time Coffee Lab opened. The market is always eager to learn, and I don’t see any difficulties in selling specialty coffee to people who come here. We have a different attitude toward customers who don’t appreciate specialty coffee at first. It’s natural; if people don’t react differently to your coffee, something is wrong. It means you’re not doing coffee that is that different from what they are used to drinking. You have to expect that. And, in order to deal with that, we have special ways of opening the customers’ minds to this new universe. I’m a shrink, so I use some psychology when I train my baristas on how to approach coffee with new customers. For example, there are words that they can’t say because they will evoke something in the customers’ sensorial spectrum that will do a disservice to what we set out to do here. We have rituals that involve comparison of different coffees. Our baristas have to pass tests before they can lead that ritual. Because a poorly led ritual will only convince the customer that the coffee she’s used to having is better than the one served here.

The coffee business, in general, is very narcissistic, meaning that we tend to think that since we have a great product, we don’t have to do much to convince customers to consume it. We forget that we need to make the customers understand and embrace that new universe. So we need to use the sensorial spectrum that the customer already has. And there will be people who won’t like it anyway, which is totally fine. We need to focus on those who will.

What made you quit working with wholesale accounts and focus only on providing courses?

It was just a matter of business focus. We realized that we were spending about two-thirds of our time filling wholesale orders, but it represented only one-third of our revenue. So it wasn’t wise to keep going. Also, it wasn’t my call either. In order to provide a good wholesale service in specialty coffee, you need to be 100 percent focused on that. So I chose to focus on education, which I truly believe is our calling here. We taught more than 1,000 people last year, and we didn’t teach more because we were doing renovations here. This year we are in full speed.

What are the projects you are currently working on?

Growing the education part of Coffee Lab. I want now to focus on creating content in videos, online, books, whatever. I see very few coffee-dedicated schools around the world. I want that to be part of who we are. We are already achieving it. We have four classrooms that are often fully booked.

You were a specialty coffee pioneer in Brazil. What is the specialty coffee community like today? Where is it heading? What is it missing?

We are growing. It’s funny because the events are getting bigger here, we see more and more people opening places dedicated to specialty coffee, yet we keep saying we are too small. We need to zoom out. The specialty business is pretty recent, and, given the circumstances, it’s going super-well. What is missing is what is missing from many other fields in Brazil: dedication and study. We are a producing country, so there is this colonialist footprint in the coffee business: We had slaves working in plantations for several decades. We still sort of carry that and we need to get rid of that somehow. It’s under our skin. I particularly miss collaborating. I travel a lot and use those opportunities to share. We need to talk more about coffee. Holding information nowadays is stupid. It’s not the information that is valuable, but what you do with it.

You are known in the industry for speaking your mind, but lately you have been a little out of the spotlight. What have you been working on?

I’ve been here but working behind the scenes. We had to do an extreme revamp here at Coffee Lab last year. I have never been around so much, but I was working with contractors, and also restructuring the administration, inventory, and personnel departments. I worked too hard last year, but away from the spotlight. I can’t wait to get back to roasting, tasting, serving. But unfortunately being a business owner encompasses much more than that. We grew a lot, our turnover has decreased, our school is full, but the price of all of that is me stepping away from the front stage.

Is the specialty coffee market, or the coffee-sourcing business in general, particularly challenging for women?

Women have to prove themselves all the time in this field. It’s because coffee is a technical subject, and coffee has historically been a male-dominated business. But again, we lack zooming out—the history is recent, women couldn’t vote until a few decades ago. We are progressing; it’s a matter of time. When I travel to North America or Europe, I sometimes even forget I have a gender—they treat me as the professional I am, rather than as a woman, etc. Here, of course, things are different. The business is “machista.”

Have you been treated differently for being a woman?

Well, being sexually harassed by a former boss in the beginning of my career. Like it was a given since I was his employee I would have to go with that. I quit. He offended me, underestimated me. And then there have been other things. We once had a client who was using an outsourced roastery to roast his coffee. So we went to this roastery to establish the roasting profiles for the coffees. And then there was the roastery guy who was like, “We have been doing this for many years, who are you to tell us to change it,” in front of the client. In the end, one employee at that roastery told me to carry the coffee sack myself, he didn’t help me, so I did. Even these days, some men roll their eyes when they see me.

Before opening Coffee Lab, I thought about getting out of the business mostly because of this. When I teach classes, I often feel like I need to mention that I enjoy Cuban cigars, that I am an airplane pilot. Then I see the male students’ attitudes change. I mean, we are considered the best Brazilian coffee roastery in the world, and yet I still feel as if things would be much easier if I were a man. We are much more acknowledged and respected by foreigners than by folks here. That hurts. And I often see people who once criticized me pretty much copying our service style, without crediting us. That’s really sad. I know I should be flattered, but I feel hurt. Because if I were a guy, I would be given credit. And believe me, I’m not a feminist, but it’s pretty clear that the fact that I am a young woman has a huge influence in it.

Ah! There was also this time where this coffee shop businessman said, “I’m finally getting to know Raposeiras, the Ronaldo of coffee,” meaning that I was all marketing. First I thought that this guy didn’t know much about soccer or coffee, Ronaldo was a great player. Later, at the tasting event I was leading, which he participated in, I deconstructed him in front of others, asking him specific things about coffee that I knew he wouldn’t know, something I felt I had to do to prove that I was not all marketing. I had to show off my knowledge because of that situation. Later he came and apologized.

What are your plans for the future? Is Coffee Lab finally branching out into other cities?

I really can’t say. I think about opening somewhere else, but outside of Brazil, pretty much for the possibility of roasting beans from other countries and bringing them into Brazil.* Coffee Lab is a successful venture on its own. My plans in Brazil remain focusing on the school here at the Lab. I don’t have any partners and don’t want to have. I’m not letting this high-speed business mindset get to me. I want to make choices that make sense to our core. I want to have my airplane. I want to fly, piloting, to the coffee farms. And that will eventually happen.

Any final words for our readers?

Something that worries me is the price we are paying for coffee. It’s too low. We don’t value the specialty coffee producer enough. We need to be less greedy. I’m a businesswoman; I know we have profit margins. We need to give up some of that margin. The specialty coffee community needs to rethink its relation with the producing community. We pay a lot more than our peers in the industry do. Have our margins decreased? Yes. Are we surviving? Hell yes. I still think I’ll be able to pay even more in the future. We need more than paying a “premium” in dollars for each sack. That is not enough for those guys. They will give up and find some job in the city. And then, who is going to produce your coffee? We can do better than that. How much are we willing to give up from our profit margin and pass it along to the producer?

* In Brazil, importing green coffee beans is forbidden by law.

Juliana Ganan is a Brazilian coffee professional and journalist. Read more Juliana Ganan on Sprudge.

Photos courtesy of Mariana Saliby.

The post An Interview With Brazilian Coffee Pioneer Isabela Raposeiras appeared first on Sprudge.