Imagine being convicted of a crime, sent to jail, serving your sentence, and then being released back into the world to find work. Would you take a job in a former police station, with holding cells intact and graffiti of past detainees still etched on the steel doors? This is the scenario some Rotterdam residents are finding themselves in. Whether you call it an ironic twist of fate, dark comedy, or proof of Northern Europe’s cool-headed, constructive criminal justice system, this social enterprise is called Heilige Boontjes. Locals can appreciate the double meaning: heilige boontjes is the Dutch expression for “goody two shoes” and translates to “holy beans.”

Established three years ago by a cop and a social worker, Heilige Boontjes has been helping economically and socially disadvantaged individuals by training them to work at a coffee bar. The majority are young ex-cons who have been selected for the program by city authorities. Pulling espresso shots, clearing tables, or ringing up orders, they are meant to develop skills deemed necessary to return to school or secure long-term employment, ultimately reintegrating into society.

Following the success of its first cafe, Heilige Boontjes opened a second, more centrally located space in September 2016. Now its flagship cafe and roastery, the stately white and blue-trimmed building was a police station from 1945 right up until 2016. That history adds another remarkable layer to the story, though the property’s main draw was its mere vacancy, says Rodney Van den Hengel, head of reintegration at Heilige Boontjes.

Showing Sprudge around on a visit there in autumn 2017, Van den Hengel starts by outlining the Netherlands’s general prison population: “You’ve got the bad, the mad, and the sad,” he says. “The first group makes a real business model of criminality; you won’t get them in here. Then you’ve got the mad; these people have real mental problems: schizophrenics, psychopaths, those with OCD—we’re not equipped to counsel them. So we don’t take in these two groups, but we’ve got the remaining 70 percent.”

He explains that the “sad” category often includes delinquents who have committed larceny and done so while suffering from substance dependence, poverty, and/or peer pressure. By the time participants arrive at Heilige Boontjes, however, some sadness has been channeled into proactivity. “These kids, they have to say to us, ‘I want to change my life,’” Van den Hengel says. Incarcerated for four years in his early 20s, the 46-year-old speaks from experience. As he puts it: “I used to be the kid that we try to help here now.”

He readily recounts his own turning point. “My mother was dying when I was in jail,” he says. “She got a massive heart attack. And I would have to wait 23 hours a day to go out to make the call to ask: ‘Is she still alive?’ So it fucked up my mind. I went really mental in there. You’re sitting in a room three meters long, two meters wide. These security guards would be walking around your cell door, bashing the keys on your door. Then I made a deal with good or God, however you call it. I said: ‘You leave my mother alone; I will clean up my life.’ ”

Behind bars, his self-education began: he read the Bible, the Koran, the Torah, Buddha’s writings. When he was free, he enrolled in a program to address his cocaine and heroin abuse. Afterward, having found a home in Rotterdam, he was given not welfare, he emphasizes, but a job. Decades later, as a professional social worker, Van den Hengel helped diminish a Rotterdam chapter of the Crips by creating labor opportunities for the gang members.

Suddenly, he witnessed how “a whole group accesses money without using criminality.” “That sparked something in my head—that you don’t use counselors to solve problems,” he says. “You have to use commerce.” He stuck to that belief when Rotterdam police officer Marco den Dunnen sought his expertise to design some scheme that could keep local youth out of crime. Although Van den Hengel says that Den Dunnen “was really into coffee” while he was “drinking shite,” the two came together and wrote a project plan.

Soon after, Den Dunnen became Heilige Boontjes’ director. He is supported by a board of volunteers, as well as investor Dick de Kock, famous for having cofounded the Netherlands’s most influential specialty chain, Coffeecompany, and the person Den Dunnen credits as “our coffee mentor.” In its first year, Heilige Boontjes saw 10 participants complete the program. Last year there were 20, which became the annual target. Van den Hengel is unaware of cases of recidivism among graduates so far.

He describes the rehabilitation as taking place in three stages. “The first phase is just like: ‘Shut the hell up and go work. You don’t have to tell us about your problems because we’ll see them show up in the work,’ ” he says. During this period, participants receive assistance in managing their income and securing housing and health insurance. Once “skills and personal problems are in tune, we go a step further,” he says of the second phase, which might lead to work as a roasting assistant or a busser. For the third and final phase, participants are taught how to be a barista. “And it’s not an easy training,” he adds.

On several visits to the flagship, right around its one-year anniversary, some half-dozen workers rotating shifts were racially diverse young men and women. Though most were unavailable to be interviewed or photographed for this article, they conveyed plenty in their barside manner. They all seemed professional and conscientious.

Heilige Boontjes relies on a three-group La Marzocco Linea Classic and two Mahlkönig K30 Vario grinders for the house Sumatra and the house Ethiopian-Brazilian blend. These coffees are sold by the bag, as are two single origins and a Brazilian-Colombian-Guatemalan blend called 010, for Rotterdam’s area code. One of the most popular drinks is a Moccamaster-brewed bakkie pleur, which is a colloquialism for “a cup of coffee” (and more fodder for Dutch city rivalry—Rotterdam and The Hague both claim coinage).

Besides roasting for its own customers and some business clients around the city, the company won a contract to supply middle-segment coffee to the city council. The order is so huge that it is handled off premises by a larger roastery. Yet Van den Hengel is quick to clarify: “It’s not our wish to make lots of money. It’s not our wish to drive Maseratis. Our wish is to make the best coffee possible.”

The sense of humor that Heilige Boontjes has about itself is on display too. Labels on the house brand’s soap bottles read: “Wash your hands in innocence.” Crime is not a joke, but the playfulness has a disarming effect. The bookshelves are rainbowed with spines of Agatha Christie novels. Guests have various seating options, from the cushy leather sofa near a wall inscribed with “boontje is ons loontje” (roughly: “beans are our means”), to utilitarian communal tables, ideal for groups ordering breakfast or lunch. The omnipresent staff portraits are by Léon Hendrickx, a photographer recently acclaimed for capturing drag queens in and out of drag and creating a series that conjoins his subjects’ two separate images to become an intimately acquainted couple.

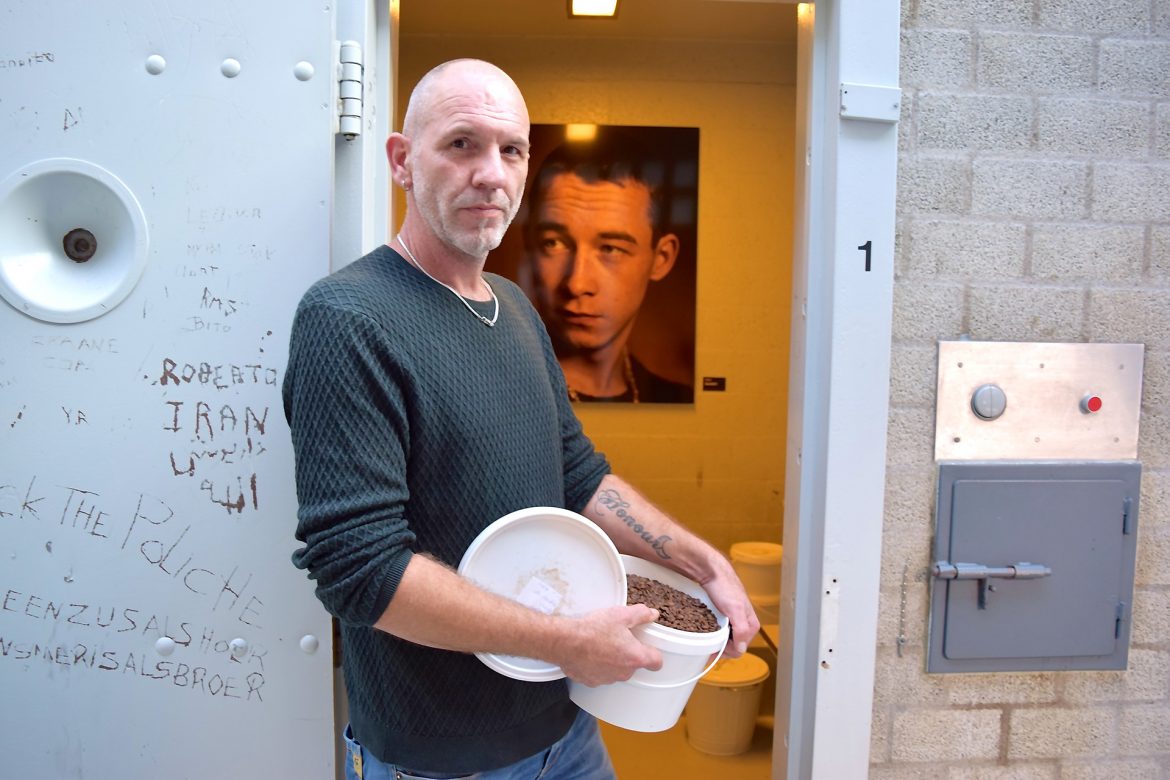

Upstairs is the roasting wing. Guard-like, the Giesen W1M stands outside the corridor of holding cells. These units are currently used for storage: one cell contains the sacks of green beans, which are supplied by Trabocca; another holds buckets of fresh roasts; next door, cupping spoons. Across the floor is the luchtplaats, essentially a smoker’s cage, functional to this day though no longer requiring a push of the red security button to let a break-taker back in.

Spending much time on this level is Robin Scholten. He was among the program’s first graduates and began as one of three roasters at Heilige Boontjes. “They saw that I was the most consistent—in Holland we call it being Pietje Precies [‘Precise Petey’],” the 27-year-old says. “I took it very seriously and they said, ‘Well, if you keep growing in that way, you’re going to be the master roaster.’ ”

Today the title is his. Lately, he has also been coaching a junior colleague in roasting. Asked if he ever foresaw coffee in his career, Scholten is straightforward. “I was a drug dealer. I was a crook,” he says. “But a couple of things happened, which I prefer to keep private, and that’s why I came here: to work on myself. Now everything is good. It’s a balanced life.” As for the familiar job setting, “Aaah, it’s good,” says Scholten. “These younger people wouldn’t have wanted to be in a police station in the past. But now they’re working in one, toward their future.”

In October, Heilige Boontjes received the Hein Roethof Prize, issued biannually by the Dutch Centre for Crime Prevention and Safety to an organization that creatively and effectively deals with a social security issue. In November, it won the 2017 Tinnen Ananas award, recognizing Heilige Boontjes as nothing less than Rotterdam’s most hospitable enterprise.

Heilige Boontjes is located at Eendrachtsplein 3, Rotterdam. Visit their official website and follow them on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter.

Karina Hof is a Sprudge staff writer based in Amsterdam. Read more Karina Hof on Sprudge.

The post Rehabilitation Through Coffee At Heilige Boontjes In Rotterdam appeared first on Sprudge.