Alfred Peet

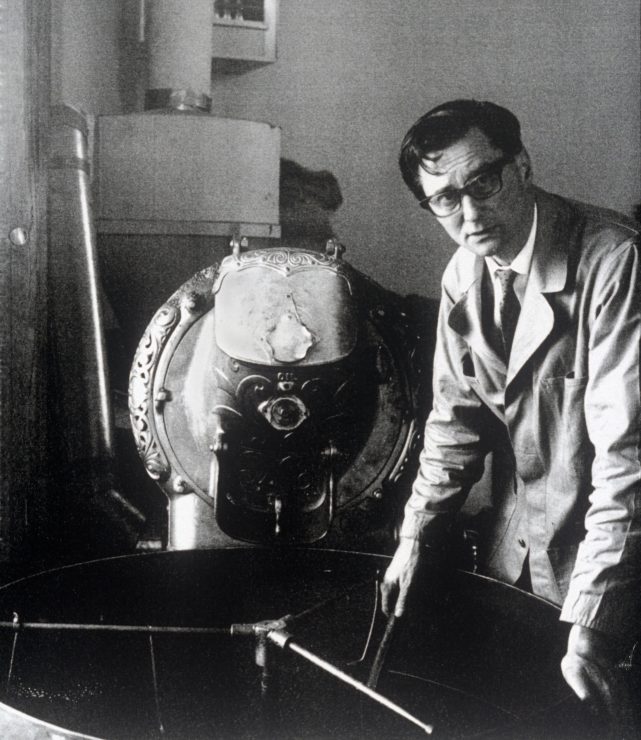

Fifty years ago, a Dutchman opened a coffee shop in Berkeley, California. He had a penchant for roasting beans dark, the way he had experienced them in Java, Indonesia, and was unwavering in his perfectionistic Old World manner of importing, roasting, selling, and preparing coffee for an American market. That man, Alfred Peet, died in 2007, though his legacy is thriving. It lives today in the business he began, Peet’s Coffee & Tea, a roaster and retailer with more than 200 locations across the US, and which owns a majority stake in well-known specialty roasters like Stumptown and Intelligentsia. And more pervasively, it lives through a company whose three founders learned from Peet everything he knew about running a coffee enterprise. That company is called Starbucks.

Peet’s, the corporation, credits its own founder with having “started the craft coffee revolution.” Mark Pendergrast dedicates his book Uncommon Grounds to Peet, calling him a “coffee curmudgeon supreme.” He is the “Dutchman who taught Americans how to drink coffee,” say industry historians. “The man who taught the world to drink coffee” is the epithet given in the title of a recently published book by Jasper Houtman, an Amsterdam-based writer and an editor at Dutch newspaper Het Financieele Dagblad. De man die de wereld koffie leerde drinken is a spry yet rigorous account of Peet’s 87 years on earth, informed by interviews with relatives, former colleagues, customers, and students (including Starbucks founder Jerry Baldwin and Peet’s roastmaster emeritus Jim Reynolds) plus archive research in the US and the Netherlands.

Jasper Houtman

Over a cappuccino at Frederix Micro Roasters in Amsterdam, Houtman told me more about this man, whose name has remained largely unfamiliar to his Dutch compatriots. Here I share highlights of our conversation, though to truly understand Peet, readers of Dutch can devour the whole book now and others should await the English translation, currently in the works. The biography brims with surprising facts and personal anecdotes that make a reader chuckle, cringe, and—every now and then—crave a cup of dark roast coffee.

Sprudge: Peet was born in 1920 into a coffee family. His father owned B. Koorn & Company, which sold coffee, tea, and spices in Alkmaar. His uncle ran the Keijzer coffee business in Amsterdam that would eventually be taken over by Simon Lévelt. Peet’s father thought his son should pursue a university education and do something scholarly. Instead, he quit school to become a “coffeeman.” Could the family have anticipated that?

Houtman: I think so because Peet was already keeping busy in his father’s shop. He liked that part of his life: heading to Fnidsen, the small street where the business was located, helping his father and doing all sorts of small jobs. You see it also further on in his life. I spoke to a journalist from the [Dutch newspaper] NRC who was living in San Francisco and visited him once. He said Peet had a room full of stuff that he liked to work on with his hands—all sorts of machines, more like creations.

He didn’t do well at school. It was not that he wasn’t intelligent, but there were other reasons. Some people say he was dyslexic, but I couldn’t find proof of that. His sister said he was a very rebellious boy and he didn’t like going to school, so that’s why he failed at school.

During World War II, Peet did forced labor in Germany. How did that play out?

A lot of Dutch people had to. Peet tried to dodge—before they sent you to Germany, you got summoned and needed to register, and he didn’t do that—but he was caught on the street and sent to work in a German factory. He worked a while there. When the laborers were allowed a few weeks of leave, Peet took it, though remained in Alkmaar, hiding out in the attic of his family’s shed. But the fact is that in the factory he needed to work and he was doing the kind of work he liked, making things, putting things together. Other workers there said to him: “Please slow down, you are working for the enemy!”

After the war, Peet had stints with tea companies in London, Java, and around New Zealand, where he also once worked as a wine sommelier. What brought him to San Francisco?

Peet said New Zealand was a boring country and that there was nothing going on. After he worked there for a few years, he wanted to go to a bigger country. Then he got his mind set on the United States. And in ’55 he arrived in San Francisco. If he would’ve gone from the Netherlands immediately to the United States after the Second World War, he would’ve ended up in New York because that’s where everyone from Europe was going. From Asia or from New Zealand, you first reach San Francisco, and in that sense, Peet’s establishment in the city was a coincidence.

After various jobs, in 1966, Peet opened up his own place: Peet’s Coffee Tea & Spices, on the corner of Vine Street and Walnut Street in Berkeley, California. Founding the business was partly prompted by his dissatisfaction reflected in the oft-cited quote: “I came to the richest country in the world, so why are they drinking the lousiest coffee?” Was he referring to the beans or the roasts?

Both, which are connected. I think he meant the quality of the coffee and that the roast was very light—which had something to do with the fact that the lighter the roast, the less loss in weight for the coffee beans and the more profit for the companies that sell coffee. But it also has to do with the quality of the beans, where they came from. He wanted good-quality coffee beans, for example, from Indonesia, and they were not available.

What influence did the San Francisco Bay Area’s Italian-American community have on a local appreciation for darker roasts?

Well, it helped. Peet knew Graffeo and other Italian local roasters, but their coffee was not put on a stage the way it was at Peet’s. They had better quality than the average American coffee and they had espresso, but it was just part of breakfast or dinner. As I understood it, the coffee entrepreneurs in that community were mainly focused on servicing restaurants and other places where Italians drink their espresso.

Peet thought of himself as a better coffeeman, one with better-quality coffee. And he made something special out of it. As someone said, he put taste back into coffee. The other thing is that he made sure people got fascinated by coffee, similar to how people were already fascinated by wine. That continuing search for the best quality and being able to make people become so interested in coffee set him apart from the other coffee entrepreneurs at the time and for years further on.

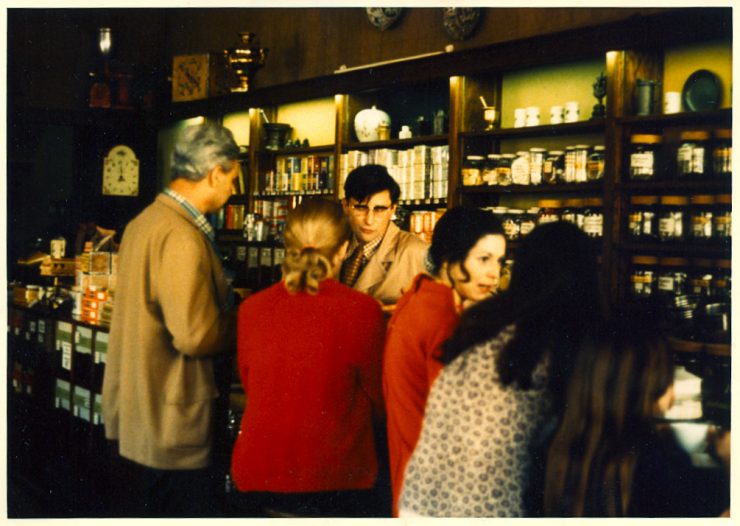

You describe Peet as having a very serious, professional demeanor. He wore a tie and a grocer’s coat, playing classical music in his shop. But when not there, his staff would play rock music, only to change it back once they saw the car of “Mr. Peet” approaching. Was his staff scared of him?

They knew they needed to listen to him, and if they didn’t, they got into trouble—it had something to do with being scared of him. Someone described it as sometimes being on pins and needles when Peet was in there. But people also laughed about it. For example, the way he showed someone how to lock the door—he gave very detailed instructions when just turning the key would be enough—people are still laughing about this at Peet’s. Still, it shows something about his commitment, his eye for detail.

Peet’s became a hippie hangout. Besides the espresso-drinking trend inspired by Kerouac’s “On The Road”, why did it have such allure?

People came from the nearby University of California, Berkeley to drink coffee there, the hippies included. But it was also the shop itself, a popular place. People took each other, saying: “Hey, we need to show you this shop, and the guy there, this Alfred Peet.”

It was the whole thing, it’s difficult to imagine. In the book, I describe it like first going inside the Blue Bottle Mint Plaza cafe, where you see all this equipment and you’re like: “Whoa, what’s happening here?” I think people got the same impression from Peet himself: he was Dutch and from the Old World, considered as having more knowledge about—more connection with—coffee than the average American. That all added up to make his shop become such an iconic place, with fans calling themselves proudly “Peetniks.”

In 1970, when Zev Siegel, Gordon Bowker, and Jerry Baldwin were seeking a consultant to advise them on, as you put it, “starting a quality coffee shop in Seattle,” they seemed to click instantly with Peet. Besides the fact that Siegel’s dad was the Seattle Symphony’s concertmaster, what did he like about these three friends who would found Starbucks a year later?

What they say is that he saw them as not just his pupils, but as the sons he never had. Peet also found it a bit fascinating—nowadays everybody wants to open their own coffee company, it seems, but back then that was completely not the case. So there were three youngsters coming all the way to Berkeley to learn a profession from him to start a company in Seattle. In a matter of weeks, during the holiday season of 1970, they learned how he ran his business. Baldwin also learned how to roast coffee.

Later, Peet went to Seattle to have a look at how things were going and he also taught them there, so there was this teaching dynamic between them for quite a while. They say they had asked his permission to model their first stores exactly after his in Berkeley. Since then, there was an interesting relationship between both companies, and lots of respect.

For a while, the two companies were even combined when, in 1984, Starbucks bought Peet’s. Starbucks’ two remaining founders, Baldwin and Bowker, were thrilled, especially Baldwin, who saw Peet’s as the big example: the company that started it all for the specialty movement. Later on, he decided to sell Starbucks and stay with Peet’s.

Cupping on a visit to Kenya.

Back in 1979, Peet had sold his company to coffee entrepreneur Sal Bonavita, for an estimated $1 to 2 million. Although hired as a consultant for a while, he became quite depressed after the sale. He was 46 when he began the business and let it go when he was about to turn 60. Why so soon?

I guess he was what you call heading for a burnout, that kind of feeling. He had this very high standard and was so absorbed by his business, and then at a certain point it was too much. He thought, “Well, I need to sell the business. Otherwise, I will be stuck in it.” I spoke to somebody who was working there in the mid ’70s, and she explained how things were, how one time he was yelling at the staff and you could see tension building up. He talked later about the selling of the company very rationally, like it was the selling of a house. But I also heard stories that he was very emotional about it and said it was like giving away your child.

Peet maintained a withdrawn lifestyle in Berkeley and never married. How were things going on a personal level as he was becoming this famous coffee entrepreneur?

He was, in general, very reluctant to talk about his feelings, but sometimes he was very honest and open about that. He once said he wasn’t capable of delegating, which was his biggest failure as a businessman.

On a personal level, he said he had difficulty with intimate relationships, though he had a group of friends until the end of his life. There is this story of how he threw away the herbs in the kitchen of one of his girlfriends. He knew better: they should be fresh. That stubbornness and making decisions for someone else didn’t make it any easier to have a lasting relationship.

Some say he became bitter and grumpy at the end, but that’s not the whole story. He also enjoyed life, was very generous to people in need. Through coffee, he kept on meeting new people and did so up until shortly before he died—he still inspired them, and I think that always made him happy.

Toward the end of his life, Peet gave roasting lessons at Starbucks, in Seattle and Amsterdam. How did he feel about Starbucks?

He was critical in an interview about the size of the coffees in the US and the fact that a lot of it is milk. He didn’t mention any names then, but it was clear he was referring to Starbucks.

After Starbucks opened its roasting plant in Amsterdam [in 2002] and he had gone there to teach some youngsters, he was talking to a family member and was critical of the fact they were roasting such huge quantities and still thinking they could maintain certain standards for quality. I guess he thought they were not living up to the standards he taught them back then.

But he also criticized other coffee businesses that didn’t live up to his standards. It was some sort of love-hate relationship—because of course he knew that they were part of his legacy. He struggled with his own entrepreneurial spirit, wondering: Do you want to become big, to grow and grow? Peet thought he could maintain a certain quality and a certain standard if things stayed small.

Peet died in 2007 in Medford, Oregon, where he had been living for a while since retiring. If he were still alive eight years later, what would he think about Peet’s acquisitions of Stumptown and of Intelligentsia?

I think he would be enthusiastic about how much people are into coffee, that coffee is everywhere. Though, he would perhaps criticize others as well, thinking: “You’re not really a professional because you don’t do it the way I do it.” I don’t know if he would like all the coffee that is out there because he had quite a specific taste. The light roasts, I don’t think he would like them very much. But the fact that people know much more about coffee and that there are so many coffee entrepreneurs enthusiastically roasting their own coffee, I think he would have liked that.

De man die de wereld koffie leerde drinken (The Man Who Taught The World To Drink Coffee) is published by Business Contact and is available for purchase online. The English translation, The Coffee Visionary: The Life and Legacy of Alfred Peet, is published by Roundtree Press and is available for purchase online.

Karina Hof is a Sprudge staff writer based in Amsterdam. Read more Karina Hof on Sprudge.

Additional photos provided by Jasper Houtman and Peet’s Coffee & Tea.

The post The Man Who Taught The World To Drink Coffee appeared first on Sprudge.