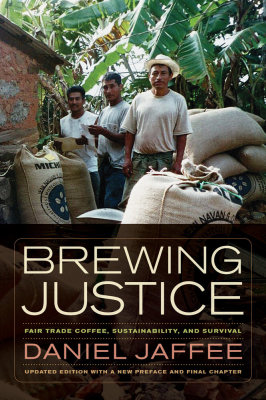

Daniel Jaffee is a professor of sociology at Portland State University. His book, Brewing Justice: Fair Trade Coffee, Sustainability, and Survival, originally came out in 2007, and a new, updated edition was released in July of 2014. An ethnography of two indigenous coffee-producing villages in Mexico, it is also a broader study of Fair Trade as a system and a movement. He begins the book by recounting his experiences picking coffee in Nicaragua in the ‘80s as part of a volunteer brigade. Sprudge contributor Nora Burkey asked him a few questions about his work.

Is picking coffee in Nicaragua what first got you interested in writing about coffee?

It wasn’t the catalyst for the work on Fair Trade, but it was my first window into the political economy of coffee. My research on Fair Trade came out of a combination of my academic interests and my previous activist commitments. During my master’s degree, I did research in Mexico on the social and economic impacts of trade liberalization, NAFTA, and the opening of markets in Mexico, especially as that affected rural and indigenous communities. Fair Trade had just arrived in the United States, and I thought it was a promising alternative to free trade as a real partnership between Northern consumers and Southern producers. In my PhD dissertation and the book, one of the main questions I address is whether having access to Fair Trade markets ends up contributing to a more socially just and ecologically sustainable cup. Does it encourage producers to protect biodiversity? For example.

And what did you find in respect to biodiversity?

In the region where I did research for Brewing Justice—Zapotec indigenous communities in the Sierra Juárez of Oaxaca, Mexico—indigenous producers are cultivating highly biodiverse, passive organic “coffee gardens.” For members of independent cooperatives participating in the Fair Trade market, most of these parcels are also certified organic, involving practices that deter soil erosion, trap organic matter, and increase both biodiversity and yields. In Mexico as a whole, studies have found that since 1989, when the International Coffee Agreement collapsed, prices crashed, and the government coffee board, the Instituto Mexicano del Café (INMECAFE), disappeared, peasants and indigenous coffee producers have been gradually shifting from a simplified shade system to increasingly biodiverse parcels.

How does this relate to Fair Trade?

During the recent coffee price crisis of 1999-2005, the extra capital from Fair Trade sales helped organized producers to sustain production while many of their unorganized neighbors selling to the conventional market were abandoning shade coffee plots and even beginning to clear them to plant corn or other crops. I found that Fair Trade households weren’t better off in terms of income, and cooperative members had to super-exploit their family labor to keep the organic production system going, which isn’t sustainable in the long run. But, cooperative members invested in Fair Trade and organic productions saw more of a future in coffee and were not clearing their coffee parcels.

You talk a lot about allegiance to the organization being a very important thing for farmers, but I think many consumers often believe allegiance to Fair Trade has to do with the price.

The Fair Trade minimum price, set by FLO (now Fairtrade International) remained virtually stagnant in nominal terms for almost 20 years, from 1988 to 2007. All that time, it was losing purchasing power to inflation. It has been raised a few times since then, in response to pressure from the producer assemblies within Fairtrade International, but it has not recouped its original 1988 value. The minimum price would need to be around $2.60 or $2.75 today in order to retain the value it had when the movement was founded. In the Oaxacan communities I studied, a higher Fair Trade minimum price would have helped producers do more than just break even. Yet, I found there are other reasons for small producers to be a part of Fair Trade. In the communities I studied in the book, Fair Trade producer families were less indebted and more food secure.

Your book has a chapter dedicated to coffee labor. Can you talk a little about labor?

In the Oaxacan indigenous communities I studied, virtually all households produce coffee, but many of these same people also work as laborers for their neighbors during the harvest. For the organized Fair Trade producers, the extra labor involved in cultivating and wet-processing for certified organic and Fair Trade markets increases their need to hire labor, so they end up spreading the financial benefits of the fair trade premium around the community to households who don’t participate in Fair Trade.

How were Fair Trade families affected by emigration?

My research in Oaxacan coffee-growing communities found that in the depths of the price crisis in 2003, when there was an enormous amount of emigration out of coffee-producing regions, many heads of producer households participating in Fair Trade tended to remain in their communities, partly due to the higher prices, and partly due to the sunk costs in organic and Fair Trade production. However, Fair Trade did not deter migration overall, as some Fair Trade proponents were claiming at the time. In fact, the higher incomes from Fair Trade allowed some families to send members out of the region and to the U.S. Since prices have risen in the mid-2000s, though, a large number of these migrants have returned.

What do you think has changed in the industry since your first edition of Brewing Justice?

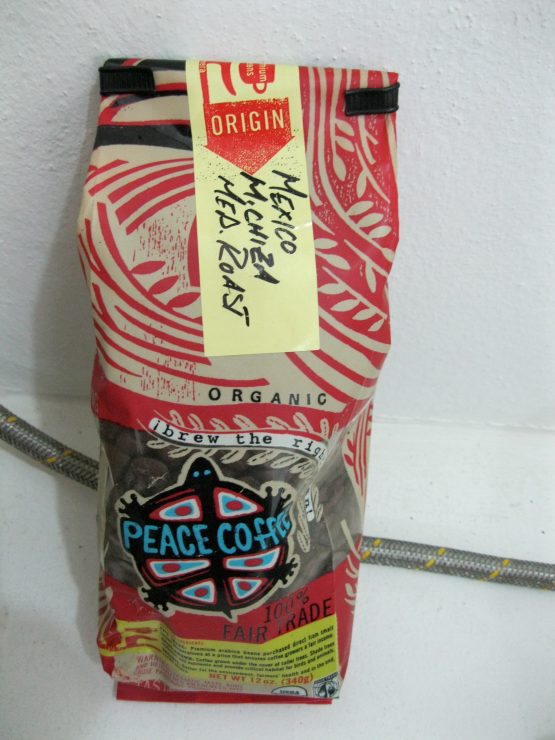

I wrote the book between 2004 and 2006, and it came out in 2007. So I was more or less writing 10 years ago. At the global level, Fair Trade has quadrupled in size to seven billion dollars a year, but many of the actors have remained the same. Equal Exchange, the Cooperative Coffee Roasters network, and Starbucks, were all present in the original edition, and they’re still involved in the struggles over what Fair Trade should mean. Another constant is the central struggle within the Fair Trade movement over whether, and to what extent, Fair Trade should be engaging with large corporate firms. Does the dramatic increase in corporate purchases of Fair Trade certified coffee represent a sign of success for the movement? Does it represent a threat? Or a bit of both?

In light of this question, would you say Fair Trade is still important?

I would say that I think currently there is plenty of attention to quality in the specialty coffee market, which makes for some absolutely delicious coffee. However, the Fair Trade movement focuses the conversation on questions of social and economic justice. We need that emphasis on economic and social conditions for smallholders, and third-party certification is a key part of ensuring that this is applied rigorously. If it is indeed true that 70% of our coffee comes from 25 million small coffee-farming families, it would be extremely shortsighted not to prioritize that.

Nora Burkey is an international development professional working in Latin America. Read more Nora Burkey on Sprudge.

The post We Talk Fair Trade With “Brewing Justice” Author Daniel Jaffee appeared first on Sprudge.